DEEP-SEA MINING: A LATENT THREAT TO OUR OCEANs

By: BCI

Deep sea mining is one of the biggest threats for our oceans and the life on our planet. Baja California Sur is the nearest place from the area that has the biggest interest for the international corporations, but represents a number of serious environmental and social threats to our region.

One major concern is the alteration of the seabed and the removal of sediments to extract minerals could destroy vital marine habitats; the dredging process and the pollution derived from heavy metals and chemicals used in mining could cause the degradation of water quality, affecting not only marine biodiversity, but also fishing, which is a crucial economic source for our local communities.

In addition, the alteration of natural sedimentation processes and the potential release of toxins could have long-term effects on the health of corals, mangroves and seagrass beds, essential for the ecological resilience of the region. Our coastal communities dependent on marine resources with the conservation and ecotourism initiatives that have grown in Baja California Sur, contrasts with the extractive model of the Deep Sea Mining.

BCI joins the international and national efforts to inform our communities and support the Mexican government to keep working on the protection of the Ocean, the land, the biodiversity and us.

What is deep-sea mining?

Thanks to technological advancements, we are now capable of exploring the most unreachable depths of the ocean, places we once could only imagine. This newfound access has revealed a world teeming with life adapted to extreme conditions, such as high pressure and temperature, as well as vast reserves of valuable minerals like copper, zinc, gold, cobalt, nickel, manganese, and other rare elements that had remained hidden until now.

This discovery has drawn the attention of corporations eager to develop a new industry: deep-sea mining, which for decades has been seeking authorization to exploit the ocean floor.

However, if this practice begins, it could destroy entire ecosystems and cause irreparable consequences, not only for marine life but also for the sustenance of life across the planet.

The seafloor is covered with billions of polymetallic nodules, a mixture of cobalt, nickel, manganese, and other rare earth metals that could help address the climate crisis. Image: The Metals Company.

HOW IS DEEP-SEA MINING CONDUCTED?

Imagine heavy machinery descending thousands of meters below the surface, scraping the seabed to collect rocks rich in minerals that have taken millions of years to form. Though still in the experimental stage, this activity is rapidly establishing itself as the next major extractive industry.

One of its primary targets is the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), a region between Hawaii and Mexico containing over 21 billion tons of polymetallic nodules—small, rounded rocks. According to scientific estimates, these nodules hold essential minerals, vital for technologies such as batteries, wind turbines, and other key components of the energy transition. [1]

Seafloor mining equipment manufactured by Nautilus Minerals (Nautilus). Image: smd.co.uk.

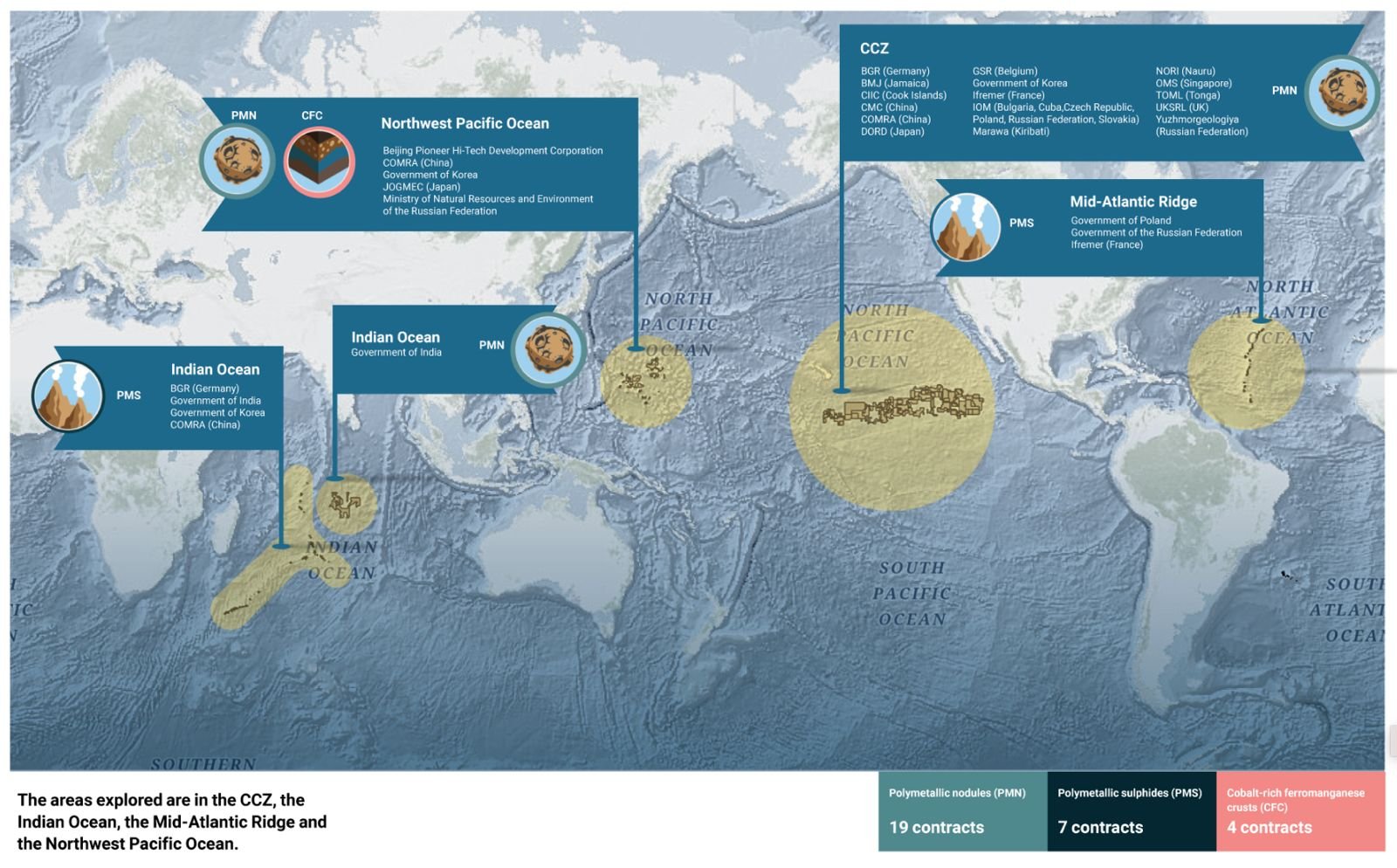

Although this is the most sought-after site due to its abundance of minerals, other areas around the world are already being explored. (Visit the map here: ISA Exploration Areas).

We highly recommend watching the documentary In To Deep, which clearly and concisely explains what deep-sea mining is and its environmental consequences. More details can be found at Deep Sea Conservation Coalition.

Recently, the Environmental Education Campus in Cabo Pulmo welcomed Farah Obaidullah, a global ocean protection activist and leader of the Ocean Hope Expedition campaign. She shared with our community the objectives of The Ocean Hope Expedition, which seeks to inform coastal communities about deep-sea mining and build a united front to protect international waters.

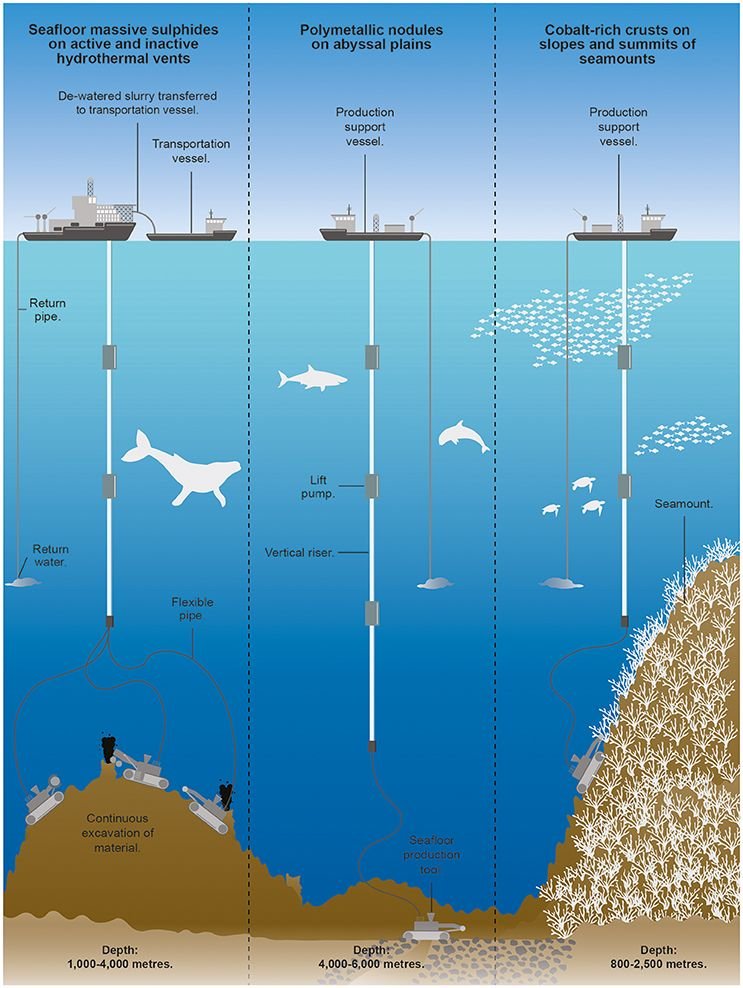

According to Farah Obaidullah, there are three main types of marine ecosystems known to host valuable minerals, many of which are currently being explored by the deep-sea mining industry:

Hydrothermal Vents

These are fissures in the seafloor located at depths between 2,000 and 4,000 meters, where hot water from beneath the Earth's crust rises. These extreme environments, rich in sulfur and adapted life forms, host valuable minerals such as copper, zinc, and gold.

Seamounts

Seamounts are underwater mountains, similar to those found on land, located between 500 and 6,000 meters deep. They are often covered with cobalt-rich crusts and other metals. Seamounts are biodiverse, supporting unique species like cold-water corals and sponges.

Polymetallic Nodule Fields (Deep-Sea Flat Areas)

These are vast areas of the seafloor covered by polymetallic nodules, which are small, rounded rocks containing valuable metals such as cobalt, nickel, and manganese. Found at depths ranging from 3,000 to 6,000 meters, these nodules are widespread but could disrupt marine ecosystems if mined.

Hydrothermal Vent – Image by: Oregon State University / CC BY-SA 2.0

Cobalt Crust on Seamount – Image by: World Ocean Review

Polymetallic Nodules in the Clarion Clipperton Zone – Image by: NOAA’s DeepCCZ project.

But does this apparent "gold mine" raise an urgent question: what are we willing to sacrifice from the depths of the ocean to meet surface-level demands?

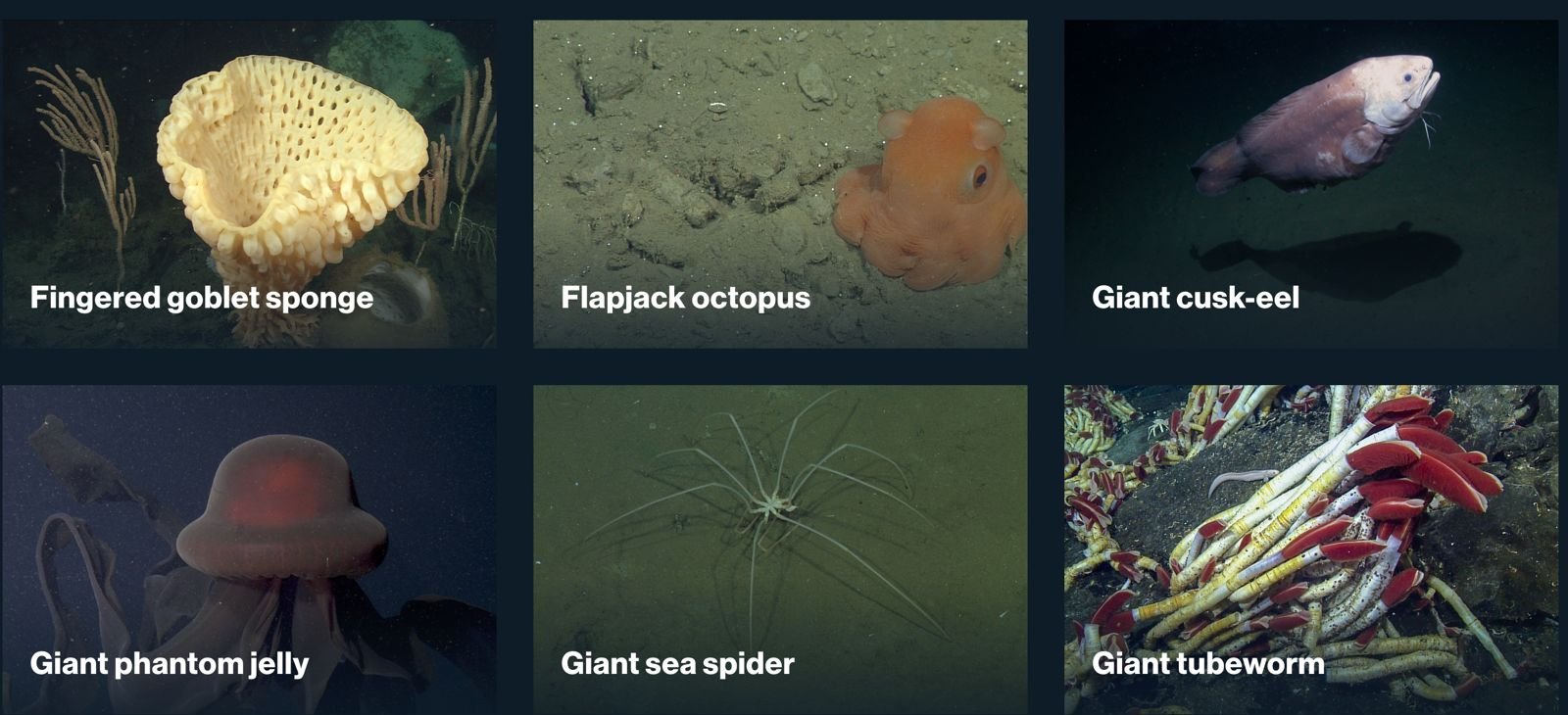

The flapjack octopus belongs to the genus Opisthoteuthis and is known for its adorable appearance and distinctive behavior, often swimming near the seafloor. It is adapted to live in deep-sea environments (ranging from 130-2,350 meters in depth) [8].

According to the Monterey Bay Aquarium, some fish like the Spiny Lumpsucker can inhabit depths of up to 1,800 meters due to their bodies being primarily composed of water, lacking spaces to accumulate air, such as lungs or swim bladders [8].

Around 90% of the species in proposed deep-sea mining zones remain unnamed. [9]

Learn more about deep-sea animals on this page from the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI), California: Monterey Bay Aquarium - Animals of the Deep

A diagram shows the processes involved in deep-sea mining for the three main types of mineral deposits (not to scale). Image by Miller et al., 2018 (CC BY 4.0). More details and the diagram can be found in the article by Miller et al. (2018) in Deep Sea Research.

Why Should We Care?

The oceans are the planet's largest life-support system. They regulate the climate, produce over 50% of the oxygen we breathe, and absorb vast amounts of carbon dioxide. However, the impact of deep-sea mining extends far beyond these depths, threatening critical functions necessary for life on Earth.

Biodiversity Loss

The seafloor is home to thousands of unique species, many of which remain undiscovered. Due to their extreme conditions, many of these species have slow reproductive and growth cycles. Deep-sea mining can lead to irreversible extinctions, particularly in sensitive habitats like hydrothermal vents [2].

Studies show that over 90% of species collected in these areas are new to science, highlighting how little we understand about these ecosystems before they are destroyed.

Destruction of Marine Habitats

Open-pit mining on the seafloor devastates habitats such as cold-water coral reefs and sponge communities, which can take centuries to recover, if at all [2].

These areas not only support unique biodiversity but also sustain essential food chains for larger marine species like sharks and whales.

Sediment Clouds

Mining operations generate vast sediment plumes that spread kilometers away, smothering nearby marine life and impacting filter feeders like corals [3].

Research indicates these clouds can cover areas of up to 10,000 km², affecting not only local species but also distant marine ecosystems.

Toxic Waste Discharge

The waste produced by mining contains heavy metals and toxins that, when released into the water column, can bioaccumulate in marine food chains [1].

This poses risks not only to marine life but also to human communities that rely on these species for food.

Acoustic and Light Pollution

The constant noise from mining equipment disrupts marine species that rely on sound for communication, such as whales and dolphins [1].

Bright lights from mining activities also affect bioluminescent organisms that use darkness for hunting and reproduction.

Disruption of Ocean Carbon Storage

Sediments rich in carbon stored on the seafloor act as natural carbon sinks. Mining could release this accumulated carbon, contributing to climate change [3].

According to the Deep Sea Conservation Coalition, disrupting these sediments could reverse decades of efforts to mitigate climate change.

According to The World Ocean Review, many species that inhabit seamounts, such as cold-water corals (pictured here), have extremely slow growth rates and produce few offspring. These corals can live for hundreds or even thousands of years, serving as crucial components of deep-sea ecosystems that are highly fragile and difficult to recover if disturbed by human activities like deep-sea mining. [7]

“ “Deep-sea mining threatens not only our oceans but the livelihoods of communities and the planet’s delicate balance. We are at a crossroads.””

WHAT IS THE CURRENT LEGAL SITUATION?

Despite the lack of strict regulation, the International Seabed Authority (ISA) has issued more than 30 exploration licenses in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), with companies eager to begin extracting resources. [2.]

These licenses have created a patchwork of concessions in international waters, effectively commercializing the seafloor.

The deep-sea mining landscape poses not only environmental threats but also significant legal and economic challenges. In September 2024, Mexico lost an international arbitration case against the U.S. company Odyssey Marine Exploration, resulting in a fine of $37.1 million. This ruling stems from Mexico's refusal to grant environmental permits for the "Don Diego" project, which aimed to extract phosphate-rich sands from the seafloor in the Gulf of Ulloa, Baja California Sur. [5.]

The Mexican government argued that the project would violate conservation principles by impacting protected species such as sea turtles and whales, as well as harming local fisheries. Although Mexico plans to appeal the ruling, this situation highlights the risks of prioritizing extractive projects over environmental protection and could set a negative precedent for other developing countries.

From the communities, we support our government to maintain a conservation-focused policy.

Hunting for phosphate: Odyssey’s eight-tonne remotely operated exploration vehicle Zeus is launched into the sea. Photograph: Reuters (amp.theguardian.com)

“Having become the fourth most sued country in the world, it is crucial that Mexican authorities take the lead from other governments who are making a retreat from the international arbitration system that makes such perverse claims possible by working toward eliminating access to such legal provisions for transnational corporations. The need is especially dire, in Mexico and globally, because of cases like this where companies use the system to seek substantial profits from projects that threaten people and the environment.“ [10]

—Jen Moore, Ellen Moore, and Carla García Zendejas, CIEL.ORG (2024)

A CALL TO ACTION

The Ocean Hope Expedition offers a clear call to action: we must unite to stop deep-sea mining before it expands on a large scale. Here are some ways to get involved:

Sign the global petition: Join the movement at change.org/nodeepseamining. Every signature adds pressure to establish a global moratorium.

Support the declaration: Organizations, businesses, and communities can endorse the cause by signing the declaration at Endosar la Declaración.

Spread the message: Print and scan available QR codes to share information with your community. [6]

Support countries like Mexico: Backing Mexico’s decision to protect our oceans from deep-sea mining is crucial. Paying the fine would set a dangerous precedent for conservation efforts in Mexico and other developing countries. [5]

Our oceans are not commodities; they are sanctuaries that regulate the climate, generate oxygen, and sustain entire communities. Protecting them is not just an act of conservation, but an urgent necessity to secure our future. Baja California Sur, with its close connection to the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), has the opportunity to lead with sustainable solutions and join global efforts to protect the planet’s last intact major ecosystem. As Farah Obaidullah emphasized during her visit, "It is here, in places like Cabo Pulmo, where local action can have a global impact."

ReferencES

Deep Sea Conservation Coalition. (2023). In to Deep.

Farah Obaidullah. (2024). The Ocean Hope Expedition.

World Ocean Review. (2023). "Sediment Plumes in Deep-Sea Mining".

Greenpeace. (2023). "Impact of Mining on Ocean Carbon Storage".

The Guardian. (2024). “How a US mining firm sued Mexico for billions – for trying to protect its own seabed”.

QR Codes y materiales de The Ocean Hope Expedition. (2024).

World Ocean Review 3. (2014). “Marine Resources – Opportunities and Risks”.

Monterey Bay Aquarium. (2024). Down to the deep.

Natural History Museum. (2023).”Around 90% of species in proposed deep-sea mining zone are unnamed”